Civilization designer Sid Meier famously said, “Games are a series of interesting decisions.” If you strictly apply that to what you can measure, the effects of your choices as they ripple across a board, then Collectionomics won’t please you. But if, by “decisions,” you include rhetoric—the art of persuasion and the battleground of opinion—then Collectionomics has the potential to scratch an itch few games can reach.

If you include…the art of persuasion and the battleground of opinion—then Collectionomics [could] scratch an itch few games can reach.

It inhabits an already peculiar subgenre which includes Superfight, But Wait, There’s More, Deception: Murder in Hong Kong, and Snake Oil. Their gameplay consists wholly of interpretation and reinterpretation. Players must be resourceful and can’t lean on grand strategy to save them. In Deception, for example, the hidden murderers and accomplices can’t sabotage missions (Resistance) or mediate through cards (Mysterium). Every detective, including the killer, gets a minute to talk about clues and one chance to pick the right ones; that minute and a strong verbal smokescreen are the only weapons in their arsenal.

Collectionomics departs from those examples, however, by breaking the “magic circle.” Designers use this term to describe the act of putting the rules of the real world aside and accepting a game’s simulation. That’s not possible in Collectionomics.

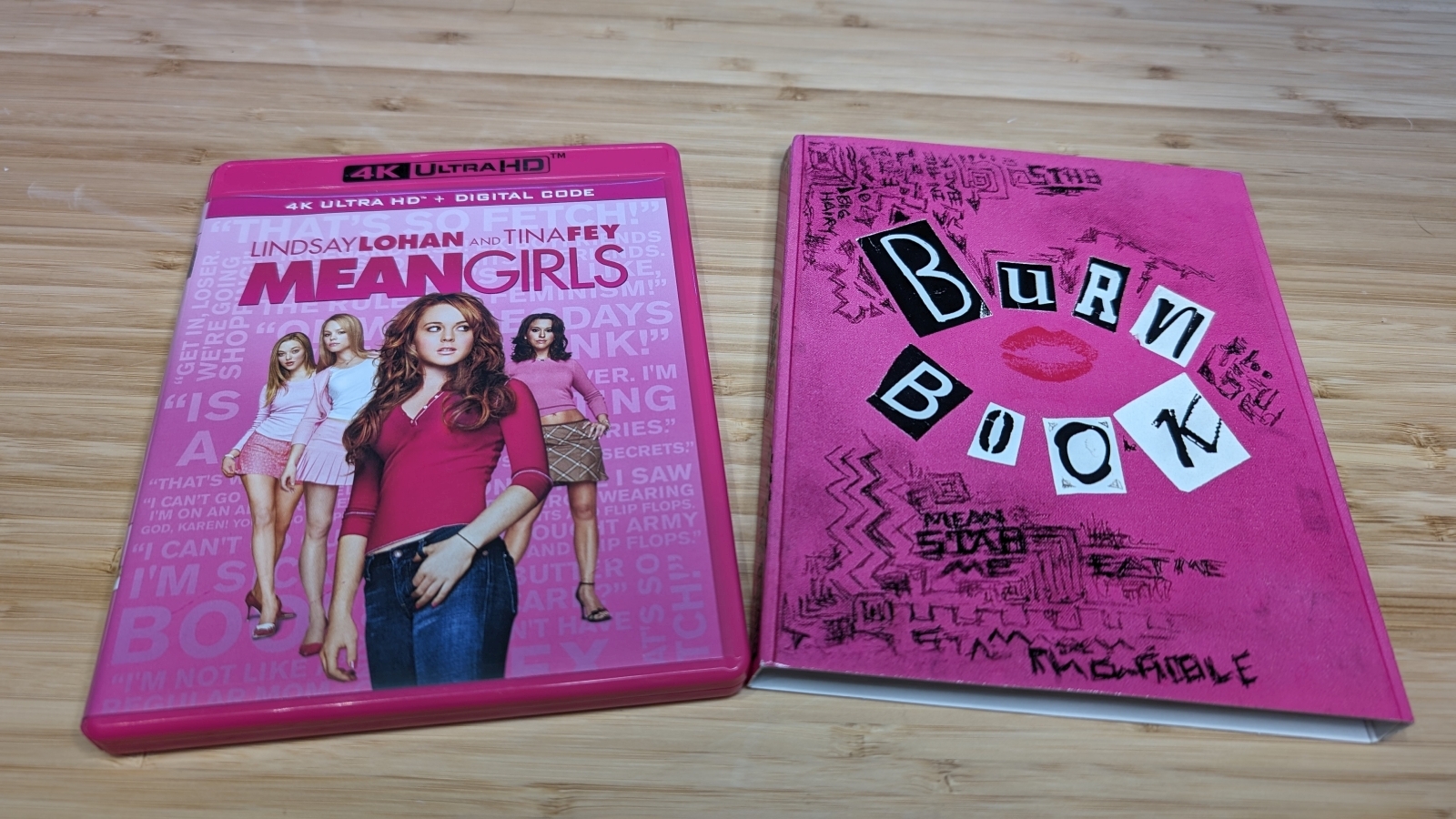

You see, the first step of playing Collectionomics involves some homework. Someone brings their hobby to the table. Regardless of what that hobby is—fishing lures, Magic cards, dice—they need to assemble around fifty items (or photos of items if the originals have a big market value). By “hobby,” I don’t mean bits and bobs from around the house. These items should be our curated pieces, the objects of private fascination, something worthy of the word “collection.” Think of the personal museums of fishing lures, vinyl albums, or railroad spikes.

Players get a random portion of those items along with a hand of cards with attributes like “Cake,” “Oscar-worthy,” or “TikTok-worthy.” They spend some actions to swap out some cards or items. Afterwards, they lay down the attributes (made anonymous á la Apples to Apples) and, considering each item in turn, debate how well the card suits it. A ballot vote and a majority pairs an item to a card, awarding points to the card’s owner.

Collectionomics…[breaks] the “magic circle.” Designers use this term to describe…putting the rules of the real world aside.

Clearly, the incentive to vote and argue for one’s own card is a problem here, and so designer Becca Horovitz includes some motivation to break patterns. Secret goal cards drive players to steer items toward certain types of attributes. Some of those secret goals want you to ensure that certain attributes never get items. These provide plenty of little nudges to break patterns and stalemates. But to my mind the most interesting secret goal isn’t written on any card at all.

Above the tug of war to score points, there’s the perspective of the collector who brought the item for appraisal. It’s silly how deep our attachment to an inanimate object can become, and those sentiments form the heart of Collectionomics.

I suppose that makes it an economic game, too. Genres can be slippery things.

Talk with the designer: the Autistic Game

Leading up to PAX Unplugged, anyone with a media badge receives dozens of invitations to playtests and personal sit-downs with designers. Frankly, most of those e-mails hit the trash in two seconds. PR blasts never had a long shelf life to begin with and it’s only gotten shorter due to the increasing volume of creatives and the dearth of writers.

I paused when it came to Collectionomics. I looked it up. Two seconds became five minutes and, mystified by my own indecision, I took Becca Horovitz’s offer. PAX was a warren of noisy rooms, I had other beats to cover, and she had a booth to run, but we carved out some time and space to chat.

Collectionomics began as a joke between friends. Becca had an overstuffed rock collection and nowhere to send it. She tossed around the idea of giving some of it away as a pledge. Sure enough, a tier on the Kickstarter will net you a chunk of that collection.

She hails from the Pitman borough of New Jersey, has always nursed an interest in gaming, and originally wanted to pursue that interest in video games. Around the Gamergate era, she became dissatisfied with the state of e-gaming and—

Here, things went squirrelly. My notes turned from rough outlines to mush. We had both taken Latin. I have a BA in Greco-Roman Studies. The conversation tipped into jargon and granular detail about the flexibility and melody of inflected languages.

I’ve given other interviews before, starting in college with a piece on the extermination of Salem, Oregon’s chinatown. Granted, it’s not my forte, but I’ve developed some instincts for how well an interview’s going. This one felt like neither a success nor a failure. Bluntly, I asked if she was on the autistic spectrum.

You see, I’m on the spectrum, too.

I was formally tested and diagnosed in 2012 with “Asperger’s Syndrome.” Asperger’s was professionally retired a year later for various reasons, the most notable being its namesake, Nazi collaborator Doctor Hans Asperger.

No two people on the spectrum are alike. “When you meet one person with autism, you’ve met one person with autism,” as the saying goes. Yet one element that unites us is obsession, our so-called “special interests.” Conversations with us sometimes feel like Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon. Nearly any topic will lead, in my mind, to antiquity studies, myths, and Baroque music. I’m aware that many of the connections to my special interest are circumstantial. I don’t, in fact, believe that I can make tupperware because I studied Roman-African pottery. Nevertheless, that special interest intrudes and then invades.

Aside from outliers like Neil deGrasse Tyson, non-autistic people can compartmentalize. Politely, they subdue their interests. They throw them in a suitcase so they can better travel along a line of thought with a stranger. In my case, most lines of thought curve into a circle eventually; all roads do lead to Rome.

Well, I like to see it as a circle, perfect and symmetrical. My wife calls it a spiral.

To put it another way, consider the concept of the magic circle mentioned above. It goes by many names. It’s everywhere in your life. In fiction, it’s suspension of disbelief. In a business meeting, it’s the agenda. These are the agreements that keep us on task and fence irrelevancies out. They are tacit agreements, at least to the autistic person.

But do games have a good idea of what’s irrelevant? I’ve written about how games keep the rest of the world at arms-length, which makes its bid for mainstream acceptance so paradoxical. One can’t stand tall in the world and refuse to be a part of it. To ask others to fold you into their lives and passions, yet have no care for the content of those lives seems fundamentally irrational.

Collectionomics asks about what we do when we’re not being “gamers.” It asks us to expose them to the uninitiated or uninterested.

I ask: Is it an autistic game?

If we can entertain the concept of a “queer” game like Molly House, one that cultivates some inkling of the queer experience to a broad audience, then why not? Believe it or not, almost everyone has a hobby or quasi-hobby. They just prefer to engineer methods to find other initiates. Consider this site, for example.

But bringing that hobby into a room with you? Flashing it in front of the unappreciative or impatient? That’s a vulnerable position autistic people know too well. Sounds like Collectionomics, so why isn’t it an autistic game?

Because the autistic experience is not one of the collections the world recognizes. We ourselves avoid looking through our own eyes. When Becca and I realized we had an opportunity that’s rare in a packed convention hall, we discarded our practiced mannerisms, the discipline that helps us survive. To use the community’s jargon, we “unmasked.” We dropped the need for eye contact and a projected ease with large crowds.

The prevailing metaphor for the autistic life is the masquerade. Hans Asperger screened minors for compatibility with Hitler’s newer, purer Germany. He argued that one type of undesirable, the “autistic psychopath,” could possibly assimilate. Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA), the most popular therapy for autism in the world, boasted that teachers had trouble picking ABA-trained kids out of a lineup.

Becca and I talked about our current masquerade, the convention itself. Without question, PAX Unplugged offers some of the finest ambassadorship when it comes to diversity. It has an “AFK Room” for the overwhelmed and stations equipped with LGBTQ+ allyship badges. Becca spotted stickers which read, “I don’t like loud noises” or “I can’t look you in the eye. Please understand.”

Consider the stark differences between those messages. On the one hand, a rainbow flair that declares a culture, that states it contributes vibrancy to our lives. On the other hand, a warning label: may be hazardous to someone’s health, yours or theirs.

Do you have this in a size “me”?

This old-fashioned medium touts personal connection as its first and finest strength. That’s what stands between it and obsolescence. Everything a cardboard chit can do, an app on Tabletop Simulator or BGA can do faster and more accurately. Our smiles, our sense of touch, and the other smudgy human fingerprints we leave behind justify these inefficiencies. Yet we leave so much about ourselves out of the magic circle. We leave out some of our best parts. We leave out entire human beings.

We leave so much about ourselves out of the magic circle. We leave out some of our best parts.

Becca’s got a few good ideas for bringing them inside. The slogan of her company, Fiat Lucre, is “Savory games for spicy people.” In her own words: “Our aim our aim to is to make games that are fun for “neurospicy” people and neurotypical people so everyone can play in a comfortable space.”

Regarding that mission’s success, I can’t speak to it untill Collectionomics hits my table a few times. But it should make us wonder what—who—we overlook in this industry. We can’t complain that there is nothing new under the sun while tilling the same old soil and checking the same old places.

The Kickstarter for Collectionomics is live and you can access it here. Happy Autism Awareness Month!

Sean Weeks fell in love with the modern tabletop scene in 2004 with Tom Lehmann's Race for the Galaxy, but his chief passions are writing, antiquity, and anthropology. You can read his work in Paste Magazine, Dicebreaker, or on his own website, www.weeksauthor.com.

See below for our list of partners and affiliates:

3 weeks ago

29

3 weeks ago

29