“Imagine someone saying ‘We need you to make a trailer for our movie, but we've only got half of the sets and props ready…” says Tim Bevan de Lange, Creative Director at Realtime Nordic, a studio that makes, specifically, video game trailers. “...and we haven’t actually shot anything, so you’ll need to do that yourself. Some of the actors won't come out of their trailers. One of them will but if you shoot him from the front you realise he's got no eyes, but don't show the audience that. It's not intentional, he's getting them fixed. Also can you film it twice, for different streaming platforms? Make a really good version for Netflix and a slightly worse looking one for Quibi.”

Every so often a game trailer comes along that makes me think, hang on, that was bloody brilliant! I bet some people made that! Most recently it was Creative Assembly’s Immortal Empires trailer. Well, I’ve been digging around and I’m happy to report that yes, although I’m the first one to just see a trailer as an algorithm trying to snatch my coin purse away like a manure-encrusted Victorian ne’er-do-well, game trailers are made by humans. They're often humans who do it as as specific job, either in-house at a developer or as an outside agency like Realtime Nordic. Enlightened and enthralled, I asked some of them about what went into the strange space that is making the trailers for your favourite games.

“Strange space is a good way of describing it,” says Bevan de Lange. “You're not showcasing something physical anyone can understand like a soda brand, and then creating associations with it looking cool and young. You're often trying to do multiple things at once. Show a narrative setup, perhaps explain complex gameplay features, make a title look visually fantastic, have something that's really compelling… but can be trimmed from 2 minute runtime to a 15 second cutdown.”

Bevan de Lange found himself in the business, he says, by fluke. He was at film school, and he’d spend the odd bit of free time playing with Machinima and Source Filmaker. Plus, he’d played a lot of PC games growing up, “messing around with console & server commands,” as he put it. The two passions turned out to be in sync. In the decade since, he's worked across a lot of titles, since agencies tend to work on more games than publishers do. “Your involvement can be a single trailer or a whole campaign of assets," he explains. "It's extremely varied - you might be in a mocap studio directing stunt performers for one trailer, then next you're wrangling a room full of players for an FPS game so that you can capture a coherent looking multiplayer match with a semblance of continuity.”

“One of the more satisfying aspects of this process is finding that perfect blend of good storytelling and amazing visuals”“One of the more satisfying aspects of this process is finding that perfect blend of good storytelling and amazing visuals for key moments that we can weave the trailer around,” says Axel Larsson, Senior Cinematic Artist at Creative Assembly. “Personally, I always like to explore the more in-between moments of the setting, like the workers in Cathay preparing for war or the council scenes in the Immortal Empires trailer. We know they ‘happen’ off camera when we play the game but to see that stuff realized always feels really awesome and fleshes out the world of Warhammer a little more.”

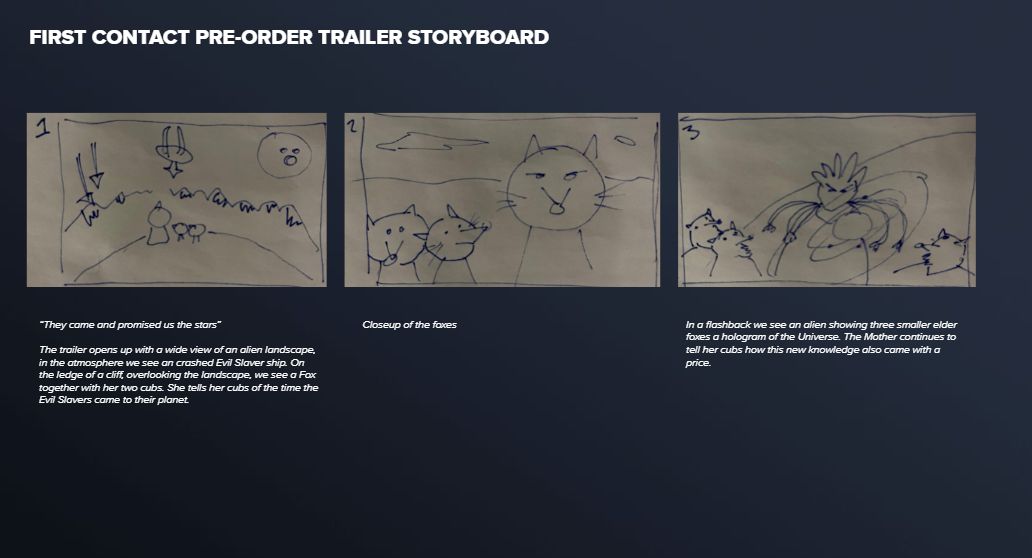

“My favourite part of the production process is the final assembly,” says Oskar Petrén, senior creative producer at Paradox - a studio I’ve always admired for their off-beat trailers - like the Stellaris one with the sci-fi sea shanty. “Working in the sound studio, tweaking those last details that make it all come together. The moment when the weird-looking storyboards and borderline cringe voice lines have metamorphosed together into the thing you imagined in your head several months before.”

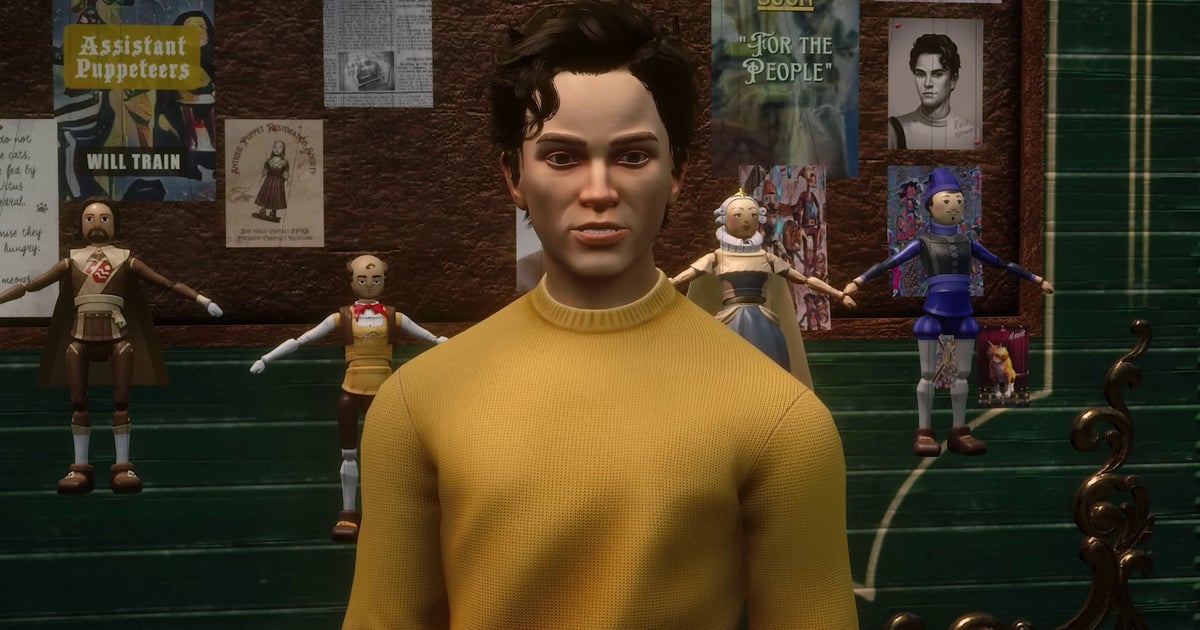

The pipeline for something like the Immortal Empires trailer involves more people than you might think. “The Cinematics team at CA is composed of 15 individuals who are often split between multiple trailers.” says Chloe Bonnet, lead cinematic animator at Creative Assembly. “However, ‘Immortal Empires’ has received work from every single one of its members at different steps of its production.” The team, says Bonnet, has three main disciplines: Animatic, Cinematic Art, and Technical Art, with leads, animators, cinematic artists, riggers, and technicians. An average trailer will go through the process of concepting, screenplay, storyboardings, animatics, art support (including rigging and character art work), motion capture, layout, environment building, and final production, versioning, and finally, delivery!

“We generally start by looking at the design documentation,” says Davide Ghelli, product marketing manager at Paradox. They aim to get a holistic view of what the design team is trying to achieve. “From there, we start discussing with them the overall player fantasy behind the game or expansion and how to transmit it. Generally, there is one nugget that sparks our imagination and leads the rest of the process from this point. A ship, a story, everything can kick off the decision on what will be in the actual trailer.” From here, they start formulating ideas for the story they want to tell. For First Contact, for example, the goal was a campaign with an overall positive tone, based on the sense of wonder you’d get when suddenly the visitors from the stars reveal themselves.

“We take ideas, and input wherever we can find it. One of the biggest pools of inspiration is listening to the devs talk about what they think are the best features, or just skimming through the development slack channel.” says Petrén. “Most of the trailers are assembled around a core idea that we build the narrative around. For Toxoids it was a gameplay gif someone posted in the slack channel, the Scavenger bots just working in space.”

“Compared to other games from Paradox where you might be locked into a certain time period, Stellaris gives you the freedom to do almost anything,” Petrén continues “There are some ground pillars to take into consideration: for example, we try to stay as true as possible to the game itself, and we of course have branding guidelines we need to follow. As long as you stay within those, anything is possible. I never imagined myself doing a Space Shanty trailer but here we are.”

At an agency it's slightly different, “The pipeline is generally along the lines of: a brief is received, and then assessed between producers and creatives. Initially you’re looking at things like timescale, budget, difficulty, resource. Do we have the people we need currently available to put together a good response?" Bevan de Lange explains. You need to pitch a great idea, that's also been well thought out in terms of how you'll execute it, because you might start production in a matter of days. Submitting an underbaked idea can lead to unnecessary stress down the line. Bevan de Lange says that “this is particularly important when you’re working on mid-development cycle games where there’s sometimes a gulf between what exists in a state that’s 'ready for primetime' vs still in development, or not feature complete.”

Broadly speaking though, consumers aren’t the fondest of adverts - though traditional advertising is at least recognised by awards like the British Arrows as, effectively, micro pieces of filmmaking and narrative. The world of gaming awards offers no such accolades. Perhaps this is because we still view any form of video game promotion with a higher degree of suspicion than most industries. Not for nought, either: we’ve likely been burnt at least once or twice in the past. Now even casual players can tell you the difference between pre-rendered and in-engine footage, between actual and cinematic gameplay, which I estimate is 20% out of interest and the rest from a place of pure, burning suspicion.

“What you do or don’t show is always part of the conversation when marketing the trailer. This can be specific story stuff or it can be more general 'nothing from this mission onward' or 'don’t show this biome'," says Bevan de Lange. "Sometimes I’ll advocate for ignoring or bending these guidelines if I think it’ll make for a better trailer.” But generally the job still means you have to work from what actually exists. “If you’re doing a cinematic trailer, you might be creating custom animations, cameras, or lighting for the game," he explains, "but ultimately the characters will be doing things the game allows them to do - or canonically they do offscreen etc. And you’ll be using most of the same art assets to create that trailer.”

Bevan de Lange says he once shot a launch trailer for an AAA game bankrolled by “one of the big 3”. After seeing it, he was told “effectively, ‘this looks great - but we’re concerned it looks better than when we play it on our platform.’ And I had to basically say ‘No, looks that good - you need to go to this location, at this time of day, during this story beat/weather condition etc to replicate that’ so that they were reassured we were being honest with consumers. Publishers are pretty hot on that stuff - nobody really wants to fall afoul of disappointed players, or advertising laws generally.”

So, it seems sometimes at least, the big publishers are just as concerned about not accidentally selling you snake oil as you are. It’s a strange line, I know, between art and advertising. A strange line between honest passion to get an audience as excited about a work as the creatives behind it are, and pure marketing. It’s a line that, if nothing else, I’ll find myself thinking about more often now.

“Being thrown into the deep end early on with the Warden and the Paunch trailer is still a highlight for me,” says Larrson, “I managed to find myself as the mocap actor for both Grom, Eltharion and all other goblins in that trailer. I had never done mocap before but it was incredibly fun to let loose as those characters.” This aside, Larrson says, he and the team are still riding high off the reaction to the Immortal Empires trailer, even from Warhammer fans who don’t play Total War. For many, it felt like the closest thing to a Warhammer fantasy movie they’re likely to see for a while. Oli Rea and Carl Allen of Creative Assembly, cinematic generalist and lead cinematic animator respectively, bring up past work on trailers like The Vampire Coast and The Shadow and the Blade, and how the best part of the job is still bringing the Warhammer world alive for the fans.

“It's a bit like someone smushed all the creative possibilites and technical pitfalls of making games and films together,” says Bevan de Lange. “I would never call what I do "art" because that feels incredibly pretentious, but obviously it is in the sense that it's an incredibly subjective space to work in.”

1 year ago

152

1 year ago

152